|

||

| Scientists' Contributions | ||

First published in the Japanese magazine OHM, 6th March 2005. Copyrights in Japanese are with OHM until three month after publication. All other copyrights are with the author. Jørgen S. Nørgård, jsn@byg.dtu.dk .

Revised version, 12th March 2005.

TECHNOLOGY AND FAIRY TALES

Jørgen Stig Nørgård, associate professor

Technical University of Denmark

"I don’t know that word at all" was the clear answer a student in 1829 gave Professor H.C. Oersted, when during an examination at Copenhagen University the professor asked with a smile: "What do you know about electromagnetism?". Nine years earlier nobody could have answered the question, since the concept connecting electricity and magnetism was discovered only in 1820 by the very same professor Oersted, later giving name to the unit of magnetic field strength, an "Oersted". The student was following an introductory course in philosophy, and his name was Hans Christian Andersen, later to become the world famous writer of fairy tales 1. Young Andersen’s encounter with the 28 year older Oersted was not their first meeting, nor the last. They developed a life long friendship.

NOT FOR CHILDREN ONLY

Japanese, Italians, Chinese, Germans, Brazilians - people all over the world have in their childhood heard some of the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, "The Emperor’s New Clothes", "The Ugly Duckling", "The Little Mermaid", etc, which have been translated into at least 145 languages. On April 2nd 2005 it will be 200 years since Hans Christian was born in a little house in the Danish city Odense. His birthday will be celebrated, and people will remember the fairy tales which they had listened to as children. But too few are aware that Andersen’s little stories were based on a deeper philosophy and have serious messages for adults.

When in his last year, 1875, a statue of H.C. Andersen was being planned to honour him, the sculptor made a sketch with him surrounded and climbed on by children. Andersen rejected the sketch, out of fear that people would perceive him as writing for children only. "… my fairy tales were for the older as well as for the children. They understood just the ornaments and only as mature people would they see and perceive the whole" 2. He got his way, and the statue placed in the Rosenborg Garden in Copenhagen shows him sitting reading with nobody near him.

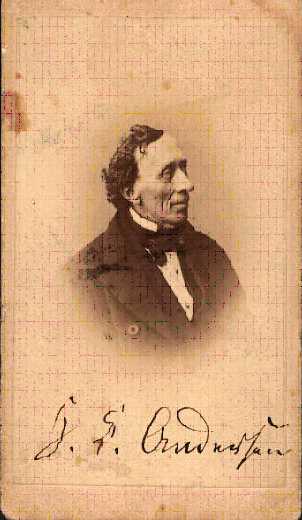

By courtesy of Odense City Museum

Even though Andersen did not like his own appearance, he had his photo

taken many times, as here in 1862. Portrait photos were often used as

visiting cards, which explains Andersen’s signature on the photo.

WEDNESDAYS AT OERSTED

Technical University of Denmark, where I have studied and worked for decades, was founded in 1829 by Professor Oersted, mentioned above. His idea was to make scientific results available to workers, craftsmen, farmers and industry for the benefit of the whole country. Oersted’s discovery of electromagnetism was not his only scientific achievement. He was, for instance, also the first to produce the metal aluminium out of clay.

The young and poor Andersen enjoyed, like many students at the time, the charity of well off families in Copenhagen. Since, however, he never married, in a way he maintained this pattern throughout his life, enjoying the friendship and hospitality of a number of benefactors. He was invited to estates around Denmark for longer stays, and in Copenhagen, where he lived, most days of the week he had dinner with one of his benefactor families. In return for the hospitality, after dinner he entertained the family by reading from his writings or by making paper cuttings. On Wednesdays the Oersted family hosted him. So, Andersen had excellent opportunities to follow the latest development in science and technology from the country’s leading person in these important fields.

In these Golden Ages of Denmark’s culture, Andersen had the opportunity to exchange views with several members of the Danish intellectual elite. Some of his contemporaries in Copenhagen are still internationally known, such as the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, and the priest and founder of Folk High School systems, Grundtvig. But it was H.C. Oersted who already in 1835 was the first to recognize the genius of Andersen and the literary genre Fairy Tales he developed. The friendship with Oersted, who was a father figure to Andersen, had a great impact on Andersen’s work. Oersted was not a natural science freak, but highly devoted also to literature and philosophy, and early suggested to Andersen that especially the fairy tales would make him immortal.

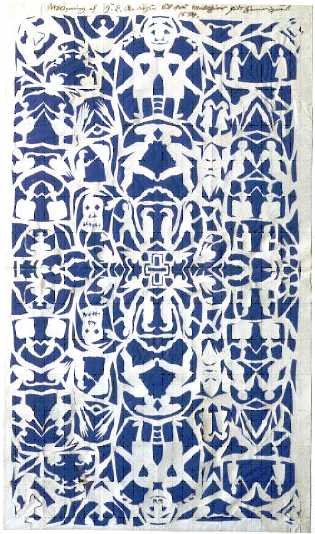

By courtesy of Odense City Museum

As appreciations to friends and entertainment at visits, Andersen made beautiful paper cuttings.

This one was made in 1874 as a present to his host during his last year in weak health.

FLYING BY STEAM

Hans Christian Andersen was enthusiastic about all the new technologies coming up in his time. He was thrilled by steam engines for ships and trains, and turned down the widespread worry, that the poetry of travelling would be gone when the steam train replaced the horse drawn diligence. Andersen wrote from one of his journeys 3 :"We now fly on the wings of steam, and before us and around us behold picture upon picture in rich succession; …. We have but to set out and dwell with all that is most beautiful, glide past what is uninteresting, and with the speed of a bird’s flight, reach our destination. Is not this like enchantment". Extraordinary for his time, he travelled to most parts of Europe, to begin with always by horse drawn carriage, but later he cheered up when his journey reached a point where the railway had been established. He could then switch from the slow, dark, crowded and dusty diligence to the fast, light and comfortable railway carriage.

Andersen witnessed many other new inventions such as the electrical generator, electromotor and telegraph, all based on his friend Oersted’s discovery of electromagnetism. Also photography was invented in that period, first by the daguerreotype technique in 1840, and Andersen had his photo taken several times.

VISION IN 1852

Just 15 years after the first railway was established, and half a century before the first motor powered airplane left the ground, Andersen wrote a small paper, In Thousands of Years, where he envisioned future transport technology 4, 5. He was wrong about the long time horizon of these technological developments, all of which have by now been realized, but otherwise he was surprisingly right in his prophecies.

In the future, Andersen imagined in 1852, young Americans would cross the Atlantic by air-steamships, faster than going by sea, to visit old Europe, ".. the country of their ancestors, the wonderful country of memories and imaginations, Europe" . At the first stop, the tourists would spend a whole day seeing England and Scotland, before continuing through the tunnel under the Channel to Paris. From there they would go on by air to Spain, Italy, Greece, Germany and – of course – Scandinavia, mentioning the historic cultural highlights of each place. Amazing, too, is Andersen’s cultural prophecy, when finishing his little travel story with a young American saying: "There is a lot to be seen in Europe!" … " and we have seen it all in eight days, and this is possible as stated in the book by the great traveller… ‘Europe Seen in Eight Days’ ". Andersen wrote this 20 years before Jules Verne wrote "Around the Earth in Eighty Days".

Most people shared Andersen’s enthusiasm about the new technologies coming up. What makes his admiration interesting is that it was coupled with a concern for the negative cultural impacts of a one eyed enthusiasm for the roaring scientific and technological development. His doubt and dilemma are reflected in many of his fairy tales, two of which are summarized in the following.

THE NIGHTINGALE

When I in the 1960s as a student lived at a dormitory, it happened that in the middle of the Danish light summer nights we went out walking silently in the forests near Copenhagen to listen to the amazingly clear and wonderful song of the little, grey bird, the nightingale. Andersen too enjoyed this bird’s song, and when he fell in love with a much-admired Swedish soprano, Jenny Lind, she inspired him in 1843 to write the fairy tale "The Nightingale". That summer the amusement park The Tivoli Garden had just opened up in Copenhagen, and Andersen’s pleasure with its illuminated Chinese style buildings is reflected in the tale, where he compares the wonder of natural song with modern technology. In a short version the story goes like this 6:

In China a great many years ago, the emperor had everything he could imagine in his porcelain palace, the most beautiful palace of the world, surrounded by a big garden with remarkable flowers. In a forest next to the palace, however, lived a little nightingale, the song of which fascinated everybody who came by during the night. Nobody in the emperor’s court knew of this bird, but when the emperor had read about this great wonder in a big book, he ordered his court to get the bird to sing for him. They searched and searched, and finally with the help of a poor little girl working in the kitchen, they found the bird. The nightingale would have preferred to sing in the forest, but agreed to perform for the emperor in the palace. The song was so sweet and touching that tears came into the emperor’s eye, and the emperor hired the nightingale.

Then one day, the Chinese emperor received a gift from the emperor of Japan. This was an artificial nightingale, looking like a living one, but covered with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. Once this mechanical bird was wound it could sing like the real one and also move its tail. Around its neck hung a ribbon saying: "The Emperor of Japan’s nightingale is a poor thing compared with that of the Emperor of China" 9*. Everyone cheered and the music-master of the court found it perfect. But after the artificial nightingale had repeated exactly the same tune 33 times, the emperor wanted again to hear the living nightingale, but she had left through an open window. But we have the best, one courtier said. And the music-master added "… that with a real nightingale we can never tell what is going to be sung, but with this bird everything is settled. It can be opened and explained, so that people may understand how the waltzes are formed, and why one note follows upon another." Only one of the poor fishermen, who had heard the real nightingale, found that in the artificial bird’s song something was missing, although he could not exactly explain what. The real nightingale was banished and "The music-master wrote a work in twenty-five volumes, about the artificial bird; which was very learned and very long, and full of the most difficult Chinese words; yet all the people said they had read it, and understood it, for fear of being thought stupid… " 6.

One evening while singing for the emperor, the spring in the artificial nightingale cracked. "Whir-r-r-r" went all the wheels, and the music stopped. The emperor’s physician could do nothing, while his watchmaker brought the bird into some order, but from then on only once a year was it allowed to have the mechanical nightingale singing. Five years later, the emperor was ill and dying. He shouted for Music! Music! But the mechanical nightingale could do noting to cheer him and remained silent, because there was no one to wind it up. Suddenly, sweet music came in from the open window. The living nightingale had heard about the emperor’s illness and had come to sing to him of hope and trust. Even Death himself enjoyed the song and gave up. The Emperor recovered.

Illustration by H. Jensenius

We might somehow adore nature, but mostly when we are sure to have the full control of it,

as here where 12 of the Emperor’s courtiers take the real live nightingale

on a trip out in "the free".

THE SNOW QUEEN AT THE PALACE OF ICE

In another of Andersen’s major works, the fairy tale "The Snow Queen" from 1844, he expresses his aversion to the tendency of putting all our trust in reasoning and the spiritually dull, intellectual life, a concern originating already when he attended high school (Latin school) at a rather mature age of 22 – 27 years 4. Summarized the story is 6:

In "The Snow Queen", two little playfellows, a girl Gerda and a boy Kay enjoy flowers and life. A demon, however, had created a distorting mirror which had the property of making everything good and beautiful shrink to almost nothing, while what was worthless and bad appeared increased in size and worse than ever. One day the mirror was accidentally broken, and millions of tiny pieces flew around to every country. Every piece retained the power of the whole mirror, if for instance it got into a person's eye or even into his heart, which then turned into a lump of ice. One such splinter of glass ended up in Kay’s eye, and another one in his heart. From that day, he gradually lost interest in playing with Gerda, and preferred to study with a magnifying glass how cold snowflakes looked like flowers rather than just enjoying real flowers.

One winter day, cool, rational thinking had estranged Kay totally from the warm friendship with Gerda, and suddenly, when he was playing with sledges with the other boys, the Snow Queen pulled his sledge along very fast. Kay was terrified and tried to say a prayer, but he could remember nothing but the multiplication table.

The Snow Queen, who in Kay’s eyes was very beautiful and perfect, carried the boy off to her palace made entirely from snow and ice, illuminated by the northern light, and soon he forgot everything about Gerda. In the Palace of Ice, Kay was busy playing The Icy Game of Reasoning, putting sharp, flat pieces of ice together in a puzzle to compose different words, and due to the bewitched splinter of glass in his eye, he saw all of the words as being very important. But one word he could never manage to form was the word “Eternity”, although the Snow Queen had promised him: "When you can find out this, you shall be your own master, and I will give you the whole world and a new pair of skates". Andersen interpreted "eternity" as somehow synonymous with "the eternal truth".

Back home, little Gerda missed her friend Kay and kept searching for him in the wide world, empowered by her own purity and innocence of heart and assisted by kind people and animals everywhere. To people she met, Gerda described Kay as very clever - he can work mental arithmetic and fractions. After a long and difficult search, Gerda finally located the Palace of Ice and slipped inside where she found her dear little Kay sitting playing his icy game, but stiff and cold. Gerda, however, wept warm tears, which melted his frozen heart and relieved his heart and eye of the tiny pieces of the demon’s glass. Kay bust into tears, and the sharp pieces of the ice puzzle danced and by themselves formed the word "Eternity". Through the help of friendly people and animals the two of them made their way well back to Kay’s grandmother, and they now found themselves grown up, yet children in heart.

Today we tend to be carried away even faster than at the time of Andersen towards pure logical reasoning. Too often we also tend to look for solutions only in the form of abstract calculations and improved technologies, having almost forgotten spiritual reflections and improved morals.

LESSONS FROM HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN

At the time of Andersen, Denmark, as most of Europe, was a melting pot of art, belief, technology and science. Scholars have tried to interpret Andersen’s stand in the debate, writing books ‘full of the most difficult words’, as Andersen himself would have expressed it. Here I will not try to draw any conclusions, but point out that through his art Andersen often seems to express feelings of doubt as well as a wish to bridge and merge different perceptions into fruitful synergy. Science can inspire belief and vice versa. Feelings can similarly interact with reasoning. Nature is the visible spirit, and spirit the invisible nature 7.

What would Andersen’s reaction have been to today’s technological and economical development and its threat to nature? God is Nature, and Nature is God was one reflection in his time, indicating that Nature has a somewhat sacred value, not to be justified by rational arguments, similar to the ethics of many of today’s environmental movements.

For myself, I could imagine that for a story like the Emperor’s New Clothes, today’s typical ‘Emperor’ would have inspired Andersen. He is ‘dressed up’ in Gross Domestic Product Growth, which every important person with high political and academic titles admires and praises, out of fear of losing their positions - until some little child yells: "…but he hasn’t got anything on" 6.

We could at the least learn from Andersen’s search for a bridge and a balance, where "... you will trust the laws of love, just as you trust the laws of reasoning", as he put it 8, reaching a point, where we do not absolutely approve and adore every new science and technology no matter what. Let us not put all our faith in the multiplication table and technological solutions, as we tend to when always asking for rational arguments. Let us in a truly democratic way allow also for opinions based on feelings, intuitions, belief and spirit. The poor fisherman, who felt something was missing in the song of the mechanical nightingale, although he could not exactly tell what, should have a bigger voice and vote in our society, as well as within the minds of each of us individually.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am grateful for the valuable comments by Lars Bo Jensen at “H.C. Andersen Centre”, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and from a few others. But I do take the responsibility for the final paper.

REFERENCES

- Andersen, H.C. (1975): The Fairy Tale of my Life, An Autobiography, (original 1868), Paddington Press Ltd., New York/London/Ontario.Andersen, H.C. (1995): H.C. Andersens Dagbøger (in Danish) (H.C. Andersen’s Diaries), Vol. X, G.E.C. Gads Publisher, Copenhagen.Andersen, H.C., (1870): In Spain and A Visit to Portugal, in Works 2, published by Hurd and Houghton, Riverside Press, Cambridge, New York.Wullschlager, J. (2000): Hans Christian Andersen. The Life of a Story Teller, Penquin Books.Andersen, H.C. (1948): Om Aartusinder (original 1852) (in Danish) in Eventyr og Historier, Gyldendal/Nordisk Forlag, Copenhagen.Owens, L. (ed.) (1984): The Complete Hans Christian Andersen Fairy Tales. Gramercy Books, New York.Andersen, J. (2003): Andersen – en biografi, (in Danish), Vol. 1 and 2, Gyldendal, Copenhagen. In English, spring 2005, Andersen – a Biography of Hans Christian Andersen, The Overshoot Press, New York.Andersen, H.C. (1871): In Sweden, in Works 7, by Hurd and Houghton, Riverside Press, Cambridge, New York.Andersen, H.C. (1942): The complete stories of Hans Christian Andersen, Vol.1: Andersen’s Fairy Tales. The Heritage Illustrated Bookshelf, New York.

The EURASAP contact to Dr. Jørgen S. Nørgård was established by Dr. Antoaneta Yotova from the National Institute of Meteorology and Hydrology, Sofia, Bulgaria. During the last years, Dr. Yotova works in the areas of policies to address climate change and communication of science. She participated in a number of international projects, for example the UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (http://www.eolss.net), where Dr. Nørgård has contributed as well.

As the Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen, whose 200-years birthday was celebrated worldwide on 2 April 2005, believed that his fairy tales were not written for children only, many scientists, and especially ones from the broad field of environmental studies, believe that their work is addressed not to scientists only. Still, the communication of research achievements to society is an issue that needs more attention in all scientific areas.

Jørgen S. Nørgård has since 1972 worked on energy planning for a humane and environmentally sustainable future. Most of this work has taken place at the Technical University of Denmark, from where he had earlier graduated and received his Ph.D. in physics and mechanical engineering. After completion of the Ph.D., he has spent more than two years in the USA, half of it at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, studying methodologies for long term dynamic analyses.

Dr. Nørgård’s research and teaching have been interdisciplinary, emphasized the environmental and economic importance of keeping energy consumption low by means of technical efficiency increases as well as by adopting appropriate lifestyles and economic structures. The methods and energy saving options he has pointed out and developed in numerous publications have increasingly been recognized internationally. He has been appointed to governmental committees and boards on energy issues, and also cooperated with various non-governmental organizations, in Denmark as well as internationally.

Over the years, invitations have taken Dr. Nørgård to many parts of the world as a speaker and advisor on energy planning. For twenty years, he has been a member of the Balaton Group, an association of a hundred environment researchers and managers from all over the world. He has published numerous writings, mostly in English and Danish as books, essays and scientific papers, just as he participate in the daily debate in the written and electronic media, about which direction of future development to choose.

|

||

| Scientists' Contributions | ||